Sign Up Now to Get Access to Our Schedule and Start Kickboxing Today

Sign Up Now to Get Access to Our Schedule and Start Kickboxing Today!

1544 N Wenatchee Ave #200, Wenatchee, WA 98801

Guaranteed Results

START YOUR TRANSFORMATION

Fitness, Nutrition & Accountability in Wenatchee to achieve the results you've always wanted!

20 Voucher Limit

Only 8 Spots Left

Transform your health, fitness, body, nutrition and life!

A membership at (Gym Name) gives you access to incredible programs, coaching and nutrition plans that help you achieve your fitness goals. you can work out wherever and whenever you want.

PROVEN 3 PILLAR TRANSFORMATION SYSTEM.

FITNESS

Expert form correction, personalized workouts, muscle-building strength and performance training, and fun fat-burning cardio in every workout.

The most effective fitness program for melting fat, toning up, and achieving fast results!

NUTRITION

We lead the way, customizing your plan for success.

Our weekly adjustments ensure consistent results, keeping you motivated.

Your fitness journey, made easy.

ACCOUNTABILITY

Your accountability coach, your teammate, always here for guidance, advice, relational accountability and encouragement.

We're dedicated to your success!

START TODAY WITH A FREE CLASS AND SEE IF ITS RIGHT FOR YOU.

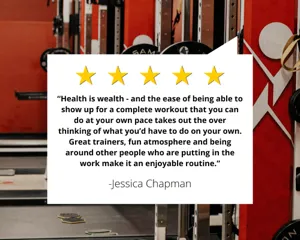

SEE WHAT OTHERS ARE SAYING!

Lose Weight, Tone and Tighten. Get Started today for free.

HOW TO GET STARTED

Step 1: Check out our 3 Pillar Transformation System tprocess above and see if we'd be a great fit for you.

Step 2: Click the button below to claim your FREE Class Voucher.

Step 3: We'll give you a call to schedule your first class!

Check out before & After photos from our

6-week challenge!

THE JUMP START YOU NEED THE WORKOUT YOU'LL LOVE.

LOSE WEIGHT, TONE & TIGHTEN.

Actualize Sports & Fitness

Privacy Policy @ 2024